The idea behind insurance is that random bad thing can happen to just about anyone, and sometimes those random things are expensive to resolve. Car crashes, medical emergencies, and flooding can destroy your personal saving and investing accounts if they happen to you and you’re not prepared to deal with them.

How Does Insurance Work?

To reduce the financial risk associated with these unexpected events, insurance companies developed programs to spread the risk among a large group of people. Each member of the group pays a fee, called an insurance premium, to receive coverage for that particular risk. If a member of the group is harmed by an unexpected event which the insurance policy covers, the insurance company will help pay for the damages. How can the insurance company afford to do that? Insurance is based on probabilities. Insurance companies expect that of 1000 people who are insured, only 2% of the people, for example, will be harmed and need compensation. So if 1000 people premiums but only 20 are harmed, the insurance company will have enough money to cover those 20 claims. In other words, insurance is a way to protect against risk.

In most situations, the insurance compensation following an event does not cover 100% of the cost incurred. The individual filing a claim for damages needs to pay a certain amount himself before the insurance coverage “kicks in.” This amount is called the deductible. Why is there a deductible? So that you will share in the risk and try to be careful with your health and your property.

There are insurance policies designed to protect against different types of risk, but they generally fall into four major categories: car insurance, property insurance, health insurance, and life insurance.

Car Insurance

Car insurance, or automobile coverage, is insurance you get to protect against risk associated with your vehicle, both while driving and when your car is parked. There are four types of car insurance: Liability, Personal Injury Protection, Collision, and Uninsured Protection. All car insurance policies are a combination of these four types.

Liability Coverage

Liability coverage is required in most states if you want to drive. This coverage exists to pay the repair and medical costs of any property or person damaged as part of an accident that was your fault. Liability coverage is required because it reduces risk for the other drivers. If you cause an accident, the other parties know that their recovery costs will be covered by your insurance company.

If you get into an accident with someone who does not have liability coverage, and the accident was his/her fault, your only option to get paid for your damages is to sue the other driver directly. Just be aware that if the person doesn’t have auto insurance, there’s a good chance they probably do not have the money to pay for the damages either.

Liability coverage does not cover you or your own vehicle. It only covers damage that you cause while driving. If you are hit by someone who does have liability insurance, their coverage will pay for your repair costs, medical bills, and other expenses, depending how much at fault the other driver was. For example, if both people in a car crash are equally at fault, each person’s liability coverage will pay 1/2 of the other driver’s expenses.

Personal Injury Protection

Personal injury coverage exists to cover your own medical expenses in the event of a car accident, regardless of who is at fault. Personal injury coverage is optional, but if you are even 10% responsible for the crash, you will have to pay 10% of your medical bills out-of-pocket if you don’t have personal injury coverage.

Collision Coverage

Collision coverage covers the repair or replacement cost of your vehicle, regardless of who is at fault. Collision coverage is generally less important than personal injury coverage, but if you have an expensive car, you will be more likely to get collision coverage to protect against potential repair costs due to a collision.

Uninsured Protection

Uninsured coverage is less expensive in states where liability insurance is required for all drivers, since it is less likely you would get in an accident with an uninsured driver.

All of the insurance coverage previously mentioned is based on the idea that if you are hit by someone else, their liability coverage will pay for your damages. However, if the other driver is not insured, you could have a lot of trouble actually getting any money to cover your expenses. Uninsured insurance protection is designed specifically to protect against getting hit by an uninsured driver. Your insurance company will cover you immediately and try to get their costs back themselves instead of making you chase the other driver for payment.

Determining Your Car Insurance Premiums

Your insurance premium is the amount the insurance company charges you for the coverages you elect to have. The cost of your premium depends on several factors, including your age, the age of your car, previous accident history, the type of car you drive, and the amount of time you spend on the road. Basically, the higher risk you present, the higher your premium cost will be. This means if you are in an age group that is more likely to be in an accident (like a young, less-experienced driver), drive a very expensive car (which costs more to repair), or have a history of getting in accidents, your premium will be higher.

On the other hand, your premium will be lower if there are several factors demonstrating you will be less likely to file an insurance claim. This includes having a history of being a safe driver, owning a car that includes safety features such as airbags and anti-lock brakes, driving a car that is less expensive to repair, and living in an area with a low crime and few accidents reported. If your car is less likely to be damaged or stolen by thieves, and if the drivers around you are also safe drivers, the risk you pose to the insurance company is lower, so your premium will also be lower.

Property Insurance

Property insurance started out as insurance policies to protect against fire, but today it also helps protect against theft, faulty construction, lightning strikes, and other potentially expensive disasters that affect your home.

Homeowners Insurance

If you own your home, you will need homeowner’s insurance. If you have a mortgage on your home, your bank or mortgage company will require you have homeowner’s insurance to help protect your investment.

Homeowner’s insurance covers your home and everything in it against damage and theft. It is there to help reduce the financial risk you could suffer due to events like a robbery, a fire, or a natural disaster. Because you have coverage, you might be tempted to file a claim if you accidentally broke your television. After all, your TV is inside your home. But remember that when you file a claim, you are responsible for paying the deductible first before the insurance company pays their portion, and that could mean you paying the first $500 which could buy you a new TV anyway.

One problem with filing a claim usually comes from proving you owned something to begin with. Insurance companies generally recommend people walk through their homes with a video recorder once per year to document everything that is in the home. By doing this, you have video documentation of your items and can use the video later to show that something was in the home before it was stolen or destroyed. While making the video, add important details verbally while capturing your footage. Simply saying something like “This television is a Vizio brand. It was purchased in November of 2019 for $600.” will help the insurance company determine the replacement value of the items that were damaged or stolen.

Homeowner’s insurance is generally more expensive for older buildings with out-of-date or unsafe electrical wiring and plumbing and for homes in higher crime areas. Homeowner’s insurance is less expensive for homes with more up-to-date insulation, new wiring, new plumbing, in safer neighborhoods, with better fire safety equipment (like smoke alarms and sprinklers), and better locks and safeguards against burglary.

Renter’s Insurance

Renter’s insurance covers your personal items when you are renting a home or apartment from someone else. The owner of the building has homeowner’s insurance to cover the building structure, so renter’s insurance is only needed to cover your property. This means that renter’s insurance is typically much cheaper. If you are a college student with mainly electronics, clothing, and a few pieces of furniture, your premium could be less than $20 per month. If a building has a fire, for example, the homeowner’s insurance would cover the building repair, and the renter would be compensated for damage or loss of their personal items through their own renter’s insurance policy.

The factors that make homeowner’s insurance more or less expensive apply in the same way to renter’s insurance. The precautions you take to keep your items safe will most likely reduce your premium cost. However, there is one factor you may not be able to control. If you are on the ground floor of a building, your renter’s insurance will probably be more expensive than someone’s on the 10th floor since your place would be more likely to be burglarized.

Health Insurance

Health Insurance is designed to cover your expenses if you get sick or injured, including all medication and hospital care. Health insurance is important. Without it, you could find yourself in tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt if an unforeseen medical emergency occurs.

Health insurance is typically provided through your employer, but if you are an independent contractor or in a lower-paying job, you may need to buy health insurance on your own. In 2010, the Affordable Care Act was passed into law, requiring that all individuals have some sort of health insurance coverage. A health care marketplace was created which allowed individuals an online place to “shop” for health insurance. Since 2014, everyone who can afford health insurance is required by law to have it unless they can demonstrate that their earnings are below a certain dollar amount and they cannot afford it.

For the elderly, Medicare is a national health insurance program that covers all medical costs of people over the age of 65. For the poor, Medicaid is a national program providing health insurance to people whose earnings fall below a certain threshold.

Life Insurance

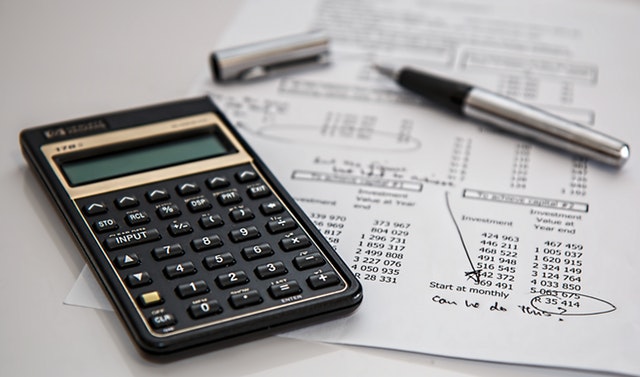

These types of life insurance policies are common both for family and retirement planning.

Life insurance was first created to provide for a deceased person’s family when they died. The insurance payout would cover the cost of funeral expenses and would provide some cash to live on until the surviving family members found other means of support. Life insurance still fulfills this role, but some policies also have a cash value. Depending on how long you hold a policy, you can receive a cash payout at the “expiration” of the policy.

For example, you may have a policy which pays $200,000 to your survivors when you die. You pay a $20 monthly premium for that coverage. If you make payments for 25 years and live until age of 65, the policy then “cashes out” and pays you a lump-sum of $50,000 to use in your retirement years.

Get PersonalFinanceLab

This lesson is part of the PersonalFinanceLab curriculum library. Schools with a PersonalFinanceLab.com site license can get this lesson, plus our full library of 300 others, along with our budgeting game, stock game, and automatically-graded assessments for their classroom - complete with LMS integration and rostering support!

Learn More

[qsm quiz=78]

Challenge Questions

- Why do people take out insurance?

- Why do the police demand that you drive with insurance?

- Using your own words, explain how insurance works in terms of demand and how people are charged.

- What is the difference between liability and deductibility?

- List 5 different things that are commonly insured.

A Commercial Bank is a type of financial institution that is responsible for catering to everyday banking needs.

A Commercial Bank is a type of financial institution that is responsible for catering to everyday banking needs.

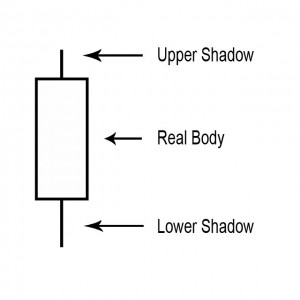

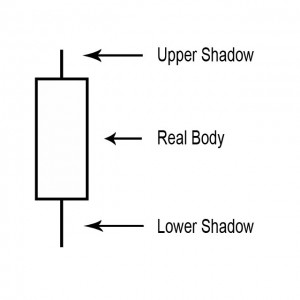

For a candlestick chart, the body or real body is the wide or colored part of a candle that represents the range between the opening and the closing prices over a specific time period (minute, hour, day, week or other). They are the most basic building block for candlestick charts.

For a candlestick chart, the body or real body is the wide or colored part of a candle that represents the range between the opening and the closing prices over a specific time period (minute, hour, day, week or other). They are the most basic building block for candlestick charts.